As the semester winds to a close, the time for reflection is upon us. While this course might be ending early for some of the other COPLAC schools, it’s ending late for us, and I feel like I can finally give it my full attention. This post is an evaluation of to what extent Baylee and I followed our project contract for the construction of our website.

Content

The pages that make up our website wound up being significantly different than what we had originally outlined. While we scrapped the “key players” section–because there were only about 3–I added branching pages to the “historical context” tab that I think are useful in breaking down the individual components that make up the case’s background. We also added the “About Us” and “About COPLAC” sections, which we hadn’t thought of when we built our contract. I feel comfortable with our deviations from the contract on this front because I think it shows a good amount of adaptation to the specific needs of our project as it developed and became more substantial.

I also think we successfully adhered to our mission statement, which was as follows:

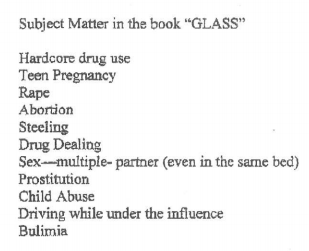

The goal of this site is to build an informative and comprehensive account of the censorship dispute between young adult fiction author Ellen Hopkins and Whittier Middle School in Norman, Oklahoma is 2009. We intend to showcase the importance of the case to the state of literary censorship in Oklahoma and locate its place in the larger framework of historical and cultural movements related to censorship.

USAO 2019 Project contract

My only lament is that our account of the case could have been far more “comprehensive” if we had the voice of the complainant. Though we were not given her name, fear still lingers with me that we could have tried a little harder to get it and track her down. If we had that, we could have a more thorough “other side” of the story and its events.

Delivery

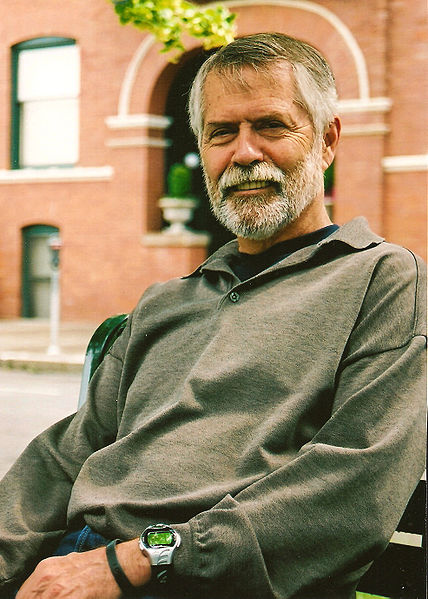

I’m extremely happy with how the visual components of the website turned out. I owe lots of this to Baylee, because the time I spent trying to figure out the colors and layouts was unproductive and frustrating. I think the images we chose are sleek and coherent with the visual scheme. We succeeded in producing the “uncluttered, professional appearance” we outlined in the contract.

Though we had a list of tools outlined in the contract, the only one we used in the final product was TimelineJS. We never did an in-person interview, so we did not use Audacity or Soundcloud at any point. While I love how the timeline looks embedded in the site, I’m sad that we didn’t get to experiment with more. I’m also still bitter about the Venngage embedding debacle, because I think clickable infographics could have added a lot to our site’s navigation scheme. However, I think the relative simplicity of the site is appropriate for the subject and the goals of the site.

We also managed to make the site easily navigable, which our contract states as a major goal. While I would have liked to include a search bar, our site probably doesn’t have a large enough amount of content to justify one.

In Conclusion

Overall, I think Baylee and I accomplished what we set out to with this site. We produced a visually-appealing, user-friendly site with a good amount of information both factual and analytical. We kept the division of labor we outlined, playing to our individual strengths, and the result reflects that. It might not be the most complicated or fancy site in the world, but it is appropriate for our topic, and I consider it to be a success.