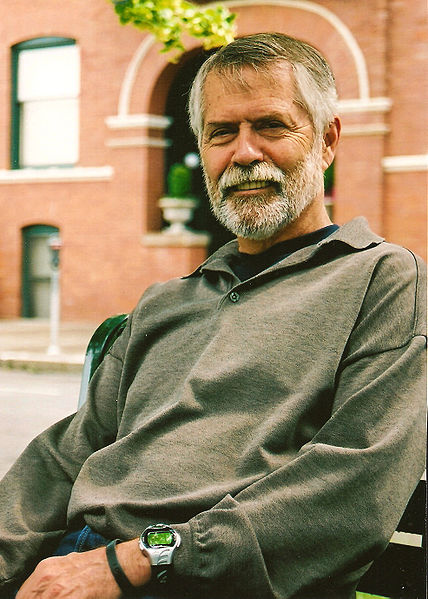

After working hard to get our website draft up and running, then annotating Telena’s site, I went back to explore some of our readings from earlier in the semester with newer, wiser eyes. I landed on Chris Crutcher’s short piece, “How They Do It,” and found many spots of relevance for our Ellen Hopkins case. Crutcher does a great job articulating many of the same themes I wanted to point out in the “significance” section of our site. Because he, like Hopkins, writes mostly for teenagers, the case where his novel Whale Talk was challenged in Fowlerville, Michigan shares some common attributes with the censorship of Glass.

“The damage had been done”

Like the case at Whittier Middle School, Whale Talk was not successfully banned from the high school in Fowlerville, but it was taken out of the school-wide curriculum whereby it was being taught. The incident even inspired some students to reach out to Crutcher and tell him how meaningful his novel was for them. Regardless, however, Crutcher maintains that censorship still occurred, despite its undramatic outcome:

The damage had been done. The flow of the project was interrupted, various teachers and administrators intimidated, and what had been a successful, innovative project, crashed. I was informed through back-channels that many teachers simply told their students to finish the book with no further discussion.

Chris Crutcher, “How they do it”

As was the case with Glass, poor administrative handling of the situation cause disruption that in itself should qualify as censorship. This case has shown me that it is important to remember that even unsuccessful censorship still limits the intellectual and creative freedom of an entire community and creates an environment that is skeptical of educators and “controversial” material of all kinds.

Philosophy over Humanity

Crutcher moves on the highlight a key, contradictory element of those who censor and challenge literature for teens: they usually don’t at all care how kids feel about it. “These people embrace their philosophy over their humanity,” he says, stressing that the massive number of young gay teens who have found meaning and comfort through his books means nothing to these parents who somehow claim they want “the best” for their children. “These folks cling to some obscure holy pronouncement that allows them the illusion of control,” writes Crutcher; these parents are so convinced that the public education system is an indoctrinating, malevolent force that they are willing to entirely disregard the wishes and intellectual needs of their own children in order to feel like they hold the power.

Ellen Hopkins expressed a similarly frustrated sentiment in one of her blog posts about the Whittier challenge. By writing about drug addiction, she asserts, she is “allowing them to live vicariously through my characters, so they don’t actually have to experience those things; literally saving their lives.” The substantial crowd Hopkins drew when she finally spoke at a church in Moore is a testament to her popularity and impact with young readers.

The key to resolving these tenuous censorship interactions between controlling parents and the institution of education, according to Crutcher, is for administrators to “stand up for their teachers before they stand up for non-educators with squeaky wheels.” I couldn’t have expressed so succinctly my main takeaway from the Ellen Hopkins case any better than this. This is what must happen to stop the ability of one parent to dictate the intellectual experiences of an entire student body.