In the last year, I decided to pursue a degree in sociology as well as my original English major. While I initially thought of these programs as distinct schools of thought, the farther I advance in either, the more they blend together. I find that I am always reading for evidence of social context, ideology, and rhetorical motive; it is not a stretch for me to read any text as political, but this thankfully does not make reading less enjoyable. Belinda Louis’s article, “Politics in Children’s Literature: Colliding Forces to Shape Young Minds,” brought to mind a myriad of sociological theories that might help explain the power dynamics that drive issues of literature’s censorship and regulation.

Past Piety

Several facets of book censorship relate back to a central idea common among conservative ideologies: the Myth of Past Piety.

Essentially, this is the faulty belief in a “golden age,” at some point in the past, where society was more morally righteous and prosperous. In our sociopolitical context, we often point to the 1950s as the “golden years” of the United States; we worship its “traditional family values” and see it as a time of ease and nostalgic perfection. This is, of course, a political sentiment; for whom, exactly, were the 1950s a utopia? Certainly not for those of racial and sexual minorities.

When access to a book for children is limited, the censorship is often to preserve the ever-esteemed “canon” of older literature which has its roots in this Past Piety mentality. As Louis suggests:

Parents feel comfortable when their children read books that the parents read when they were in school. As a result, many district lists essentially consist of award-winning, nonprovocative books from a bygone era. New and exciting titles can hardly find a foothold on district-approved lists.

It is natural for parents and even teachers to feel admiration and nostalgia for the texts that shaped their young lives, but it becomes harmful when it discourages the critical thinking and modern-day relevance that comes with adopting new and interesting works.

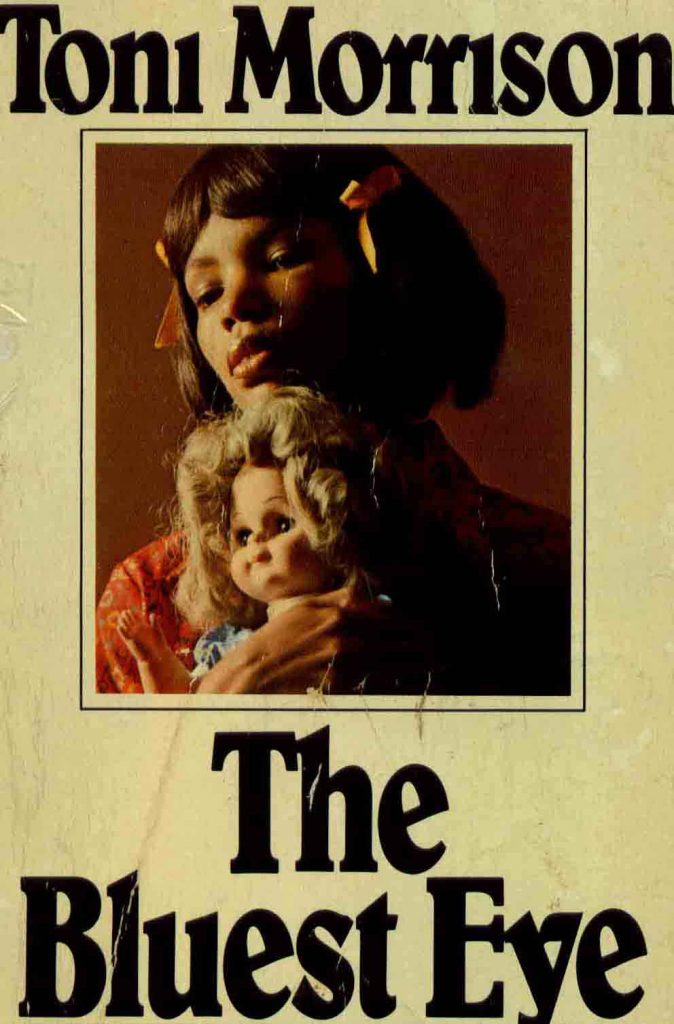

The fallacy of Past Piety also informs attempts to maintain a gleaming, idealized version of the past when presented with contrary evidence. A parent who looks fondly upon decades past might be hesitant to let his/her child or teenager read a book like Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, which suggests that the past was not so pious.

Censorship and Social Class

Sociological theories about the intersection of social class and family structure have profound implications for how parents of different socioeconomic statuses approach the education of their children. A common explanation for why children of lower-income families have more difficulty in school is that unlike middle- and upper-class parents. many working-class and poor parents lack the time or the resources to assist their children at home. In many cases, these parents spend their afternoons and evenings working to make ends meet, rather than attending PTA meetings like their higher-SES counterparts. This does not mean lower-income parents do not care about their children’s educations, but that they do not have the means to invest as much. Issues of censorship, then, become mostly middle-class and upper-class issues. Low-income and low-education parents are most likely to trust the decisions of the teachers and school boards, rather than challenge them. To challenge the inclusion of a controversial book requires free time, privilege, and power.

Leave a Reply