Geographically, the Appalachian region is defined as the area surrounding the Appalachian Mountains, located on the eastern side of the United States.

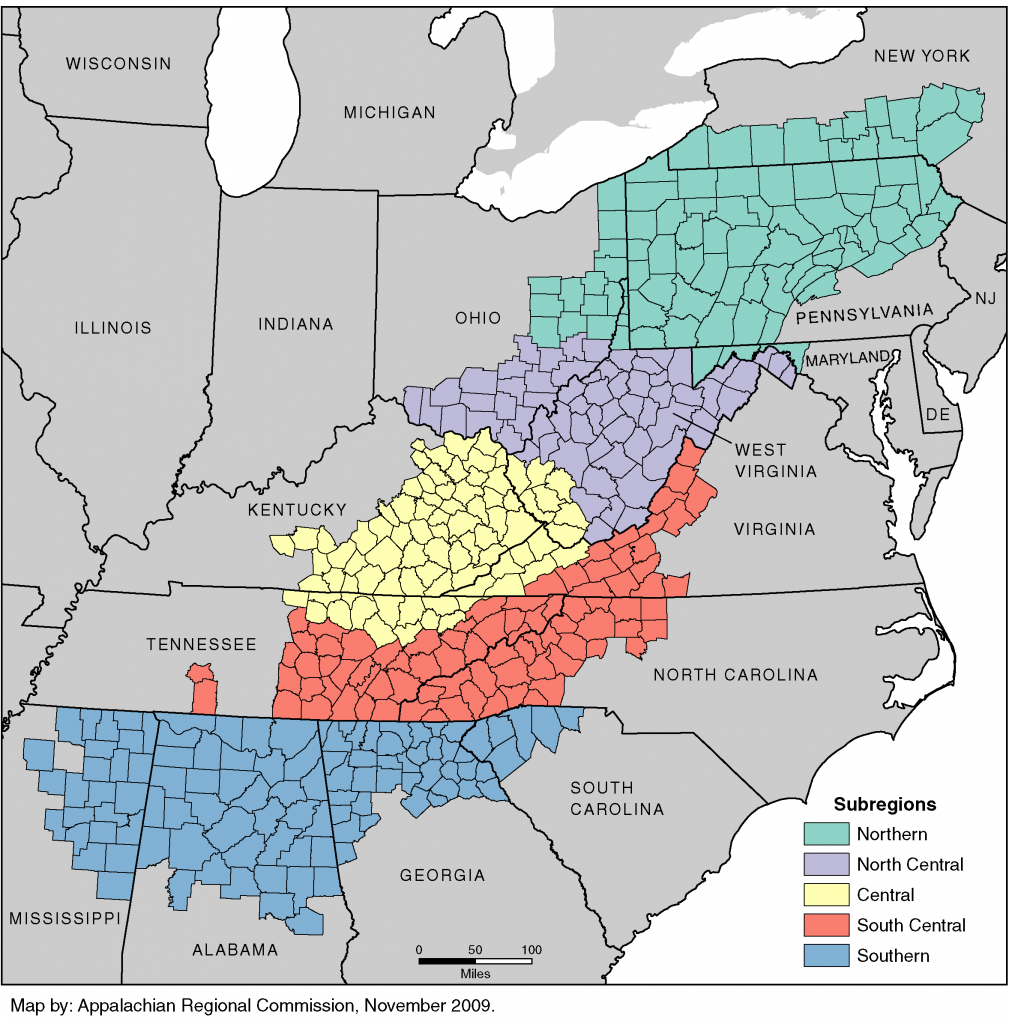

To give a more specific definition, The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), which is a federal organization created to promote economic development in the Appalachian Mountains, defines the area as a “205,000-square-mile region that follows the spine of the Appalachian Mountains from southern New York to northern Mississippi. It includes all of West Virginia and parts of 12 other states: Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia”.1

As communicated by the ARC’s map of Appalachian subregions (above), the states of the area are often divided into smaller subregions – North, Central, and South – that have similar geographical features and cultural traditions.2 The regions are very different from one another, so what it means to be Appalachian changes from one to the next.

Because the Carroll County case and The Floatplane Notebooks is deeply rooted in Central Appalachian culture, this page is devoted to briefly exploring the history of the central region.

Similar to many areas in the United States, Native Americans were the first to make their home in Central Appalachia. According to The Moonlit Road, “[a]t one time, the Cherokee Nation encompassed over 135,000 square miles of territory. As more white people settled on their land in the 1700s, the Nation shrank”.3

The expanse of the Cherokee population in the area allowed the Cherokee people to root their traditions in the area. On The Stay Project, Sam Gleaves points out that the Cherokee left behind their knowledge of how to work and use the land, as well as an appreciation for the oral tradition, long after their population had declined in the area.4 Story-telling and loyalty to the mountains are themes that remain in Central Appalachian culture today.

In addition to the Cherokee Indians, Appalachia was also settled by several different groups of European immigrants, namely the Scots-Irish.

In an article for Classroom, Joseph Cummins explains that the Scotch-Irish began to settle the Appalachian mountains in the early and mid-1700s because they were attracted to the promise of more land, food, and religious tolerance than what they lived with in Ireland.5 However, as Cummins acknowledges, when the Scotch-Irish arrived in North America, they had to learn how to survive in the mountains by grouping together in closed communities, learning how to farm mountain land, and defending the territory they settled from Native American attacks.6

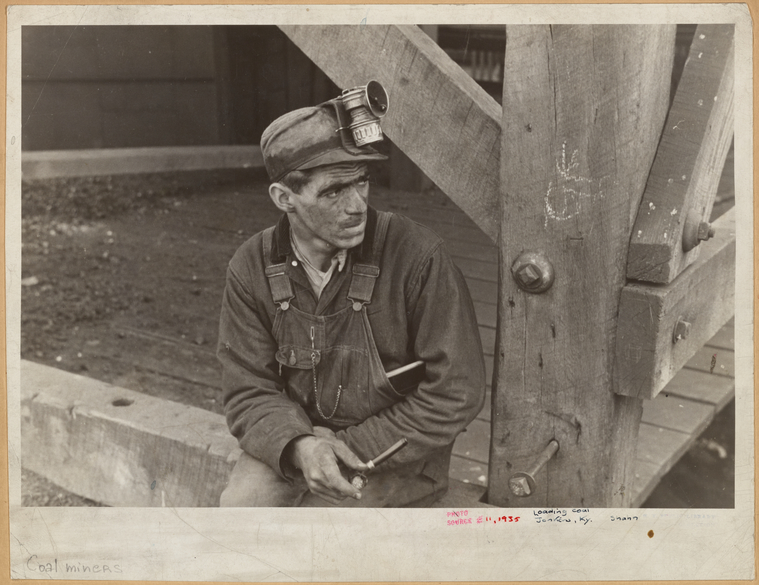

The early life of the Scotch-Irish in Appalachia can still be seen in the spirit of the culture that pervades the central region and is exemplified by the general community orientation of the area, a broad cultural appreciation for physical, hands-on work (such as farming, coal mining, or logging), and re-occurring self-descriptions of Appalachian people as resilient and persevering.

In addition to the spirit of the region, many traditions also originate from the Scotch-Irish. In “Seven generations of stubbornness,” Byron Chesney credits the Scotch-Irish for bringing over the protestant religion that is at the root of many Presbyterian and Baptist denominations in the area, and he also recognizes the monumental impact of folk music on the development of bluegrass and other genres of country music.7

Ballads and bluegrass are commonly associated with the area, and they are an important part of its history, though the tradition has continued to change and over time. Likewise, religion – specifically the Christian tradition – is a monumentally impactful part of Appalachian culture. In the words of Troy Gowen, “Cultural traits highly valued by many Appalachians are intimately tied to religious beliefs shaped by the challenges of frontier life–humility, well-defined family structure, self-sufficiency and resourcefulness, and hospitality are all encouraged by the Scriptures, and all were essential for survival in the remote valleys and mountain hollows.”8 An idea that goes back to the very beginning of Appalachian mountain settlement, faith is an trait that is well realized by the high number of small church steeples that shadow small, Appalachian towns (and even larger cities) and is reflected in the traditional, conservative ideologies of the area.

To summarize, faith, family, and community are all important aspects of Appalachian culture. However, these traits, as well as the others discussed, only begin to categorize the culture of the Appalachian region. The traits are the historical roots of Appalachia, and it is impossible to understand the Appalachian literature and life without discussing them. However, the area is also continually defined by new traditions and cultural elements. Acknowledging the history of Appalachia a step towards understanding the culture, but viewing Appalachia only in terms of its history – as many unfamiliar with the region do – ignores and limits the strength found in the contemporary diversity and progression of the area, as well as the versatility of its foundational traditions.

Citations

- The Appalachian Regional Commission. The Appalachian Region. n.d. Accessed April 6, 2019. https://www.arc.gov/Appalachian_region/theappalachianregion.asp

- The Appalachian Regional Commission. Subregions of Appalachia Map. November 2009. Accessed April 6, 2019. https://www.arc.gov/research/MapsofAppalachia.asp?MAP_ID=31

- The Moonlit Road LLC. Cherokee Native Americans in Appalachia. 05 February 2017. Accessed April 6, 2019. https://www.themoonlitroad.com/cherokee-native-americans-Appalachia/

- Gleaves, S. Central Appalachia. n.d. The Stay Project. Accessed April 7, 2019.https://www.thestayproject.com/central-appalachia.html

- Cummins, J. The Scotch & Irish on the 18th Century Appalachian Frontier. Classroom. 21 November 2017. Accessed April 6, 2019. https://classroom.synonym.com/scotch-irish-18th-century-appalachian-frontier-9956.html

- (Cummins 2017, para. 3)

- Chesney, B. Seven generations of stubbornness. 16 October 2007. Appalachian History. D. Tabler, Publisher. Accessed April 6, 2019. http://www.appalachianhistory.net/2007/10/seven-generations-of-stubbornness.html

- Gowen, T. Religion in Appalachia. 2003. Smithsonian Folklife Festival. Accessed April 24, 2019. https://festival.si.edu/articles/2003/religion-in-appalachia

Photo Credits

Figure 1: The Appalachian Regional Commission. Subregions of Appalachia Map. November 2009. Accessed April 6, 2019. https://www.arc.gov/research/MapsofAppalachia.asp?MAP_ID=31

Figure 2: Boston Public Library. Cherokee Indians, Cherokee Indian Reservation, North Carolina. 2011. In Flickr. Accessed April 6, 2019. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License (CC BY 2.0). https://www.flickr.com/photos/24029425@N06/5756035976

Figure 3: Shahn, Ben. Kentucky Coal Miner, Jenkins, Kentucky. 1935. New York Public Library. In Picryl. Accessed April 24, 2019. https://picryl.com/media/kentucky-coal-miner-jenkins-kentucky

No Comments Yet